Translation is hard for asylum-seekers. Trump is making it harder - RCT covered by Mission Local

At our language Justice Forum at the Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts in San Francisco on Oct. 30, we discuss the targeting on asylum seekers with language violence and language access. It was covered by Mission Local.

You can read the full article here. Below is a copy of the publication.

Translation is hard for asylum-seekers. Trump is making it harder.

Rules meant to protect minority cultures fleeing persecution are being discarded, warn attorneys and asylum-seekers

by Sage Ríos Mace

November 5, 2025, 4:00 am

In mid-August, Immigration and Customs Enforcement picked up and detained Elias Gonzales, along with five other immigrants, during a routine workday in East Oakland.

Gonzales spent the next two months at a Tacoma, Washington, detention facility — an experience that his attorney, Abby Sullivan Engen, said left him traumatized.

Gonzales (a pseudonym) is a speaker of an indigenous Mayan language, and struggles with a hearing problem. Within the facility, ICE failed to provide an interpreter to explain legal documents or other procedures, leaving him isolated and unsure of what was happening.

Gonzales may be legally deaf, according to his attorney.

Before Gonzales was arrested and Sullivan Engen learned of his case through the rapid response hotline, his family had hired a private attorney.

That attorney also ignored Gonzales’s specialized needs, conducted the consultation in Spanish, and filed his asylum application in Spanish, although Gonzales’s understanding is limited in that language.

As a result, the private attorney failed to capture critical details about Gonzales’s asylum claim as an indigenous person fleeing his home country.

“[The claim] doesn’t tell the most important aspects of his story,” said Sullivan Engen, co-director of the immigrants’ rights practice at La Raza Legal Center in Oakland.

Gonzales’s case, though harrowing, is not unique. Translating across language and culture has always been complicated, especially in asylum cases. Sullivan Engen said that language access in legal proceedings is a “huge concern” that must be addressed.

But as the Trump administration has escalated threats against immigrants, access to interpretation and translation services has become even harder to secure within detention centers, and throughout the legal process.

On Oct. 28, Gonzales was released from detention after the success of the habeas petition that Sullivan Engen filed on his behalf.

While his release is a victory, Gonzales must now grapple with the trauma of his detention while continuing his asylum proceedings with a “terrible asylum application that will follow him,” said Sullivan Engen.

For cases like these, the stakes are high. When an asylum seeker “cannot express themselves fully, it can result in the loss of their asylum case,” said Sullivan Engen.

Nonprofits respond to a language-access crisis under Trump

In February, President Donald Trump terminated a 2023 Biden-era directive that required immigration judges and local Homeland Security officials to connect immigrants with resources like out-of-court translation services to help them fill out and file asylum-related documents.

San Francisco immigration judges still offer asylum-seekers the same list of resources as they did before February, but now with a warning that, most likely, every organization on the list is too busy to take on any new cases.

In March, Trump revoked Executive Order 13166, a Clinton-era order that required all federal agencies to provide meaningful language access for people with limited English proficiency.

Despite these rollbacks, immigration courts still have interpreters — in San Francisco, often through in-person SOSi contractors or the remote Lionsbridge service — but there’s less federal funding for interpretation and translation services overall.

Furthermore, courts now operate without the guidance they once received from the Executive Office for Immigration Review on how to provide the kind of interpretation that asylum-seekers actually need.

The responsibility to fill in the gaps has fallen on local immigration nonprofits and pro-bono interpreters, just as they are facing unprecedented caseloads and budget cuts.

Immigration attorneys in the Bay Area often provide in-house translation services to clients, but those who take pro bono cases now have waitlists of six months or more.

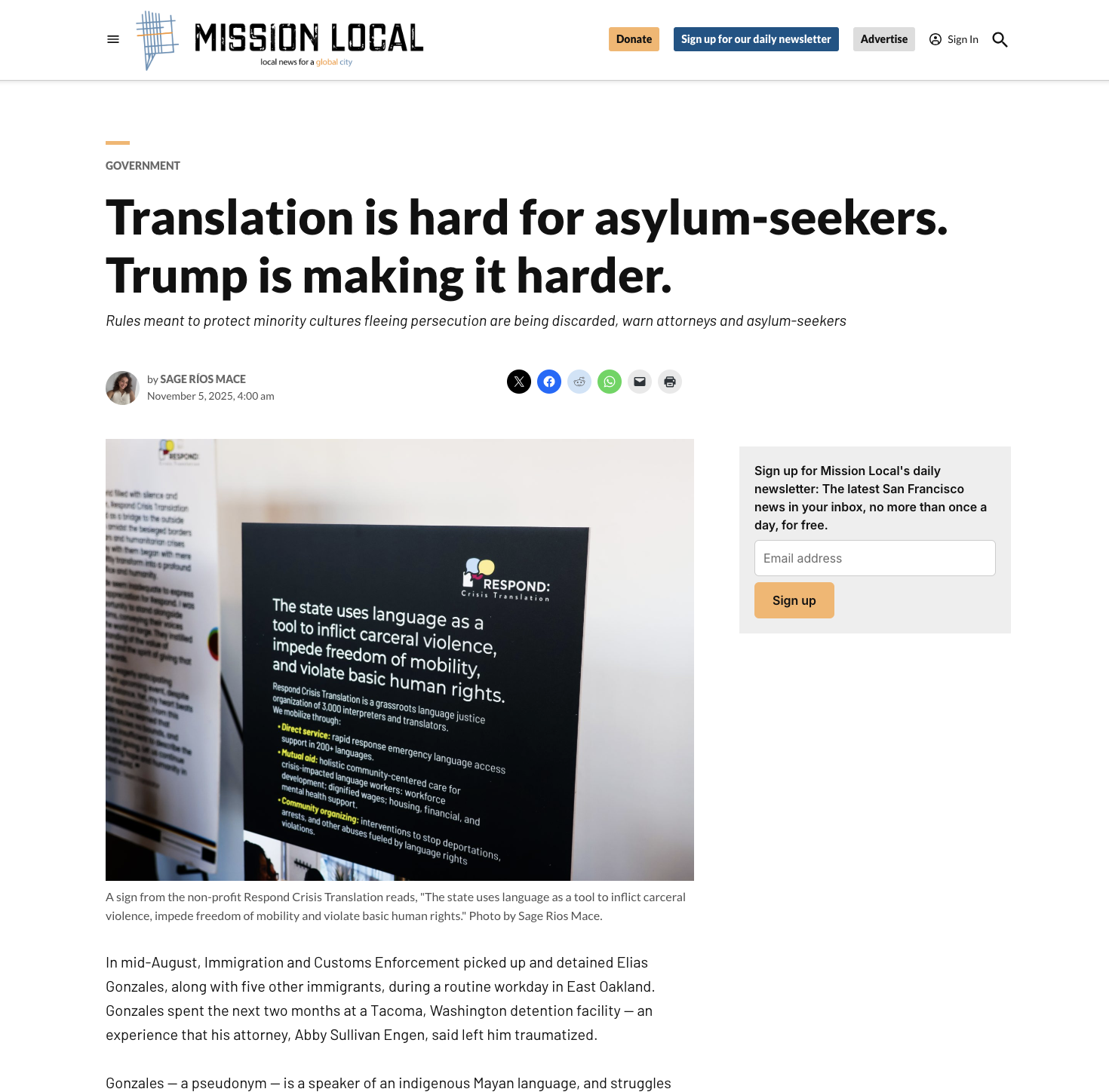

“We don’t have the luxury of a waitlist,” said Ariel Koren, who runs Respond Crisis Translation, a nonprofit that provides free translation and interpreters for a variety of situations, including asylum cases.

Due to the language-access crisis at hand, people frequently contact the organization only moments before their asylum interviews, Koren said.

Miscommunication starts at the border

The problem of interpretation starts at the border, said Sarah Gavigan, a senior immigration attorney for CARACEN S.F., a nonprofit that is part of San Francisco’s Language Access Network, a coalition of nonprofits that advocates for access to interpreters and other translation services in city government.

When a person arrives at the U.S. border to seek asylum, if they aren’t able to make themselves understood to the border agents they encounter, they are deported immediately. That deportation makes it much harder for them to seek asylum in the future.

Even after Trump’s executive orders, U.S. Customs and Border Protection is supposed to provide migrants with basic interpretation services after they have been detained at the border. But, said Gavigan, this rarely happens, and didn’t happen even under prior administrations.

When someone claims asylum, CBP gives them a Form I-770 that is a notice of their rights like the right to use the telephone to call a loved one as well as the right to an attorney and the hearing process.

Gavigan, who works with unaccompanied minors, has never seen the Form I-770 in past clients’ language of Mam, she said. Frequently, she has seen Spanish-speaking children receive the I-770 in English.

Asylum seekers often rely on interpreters at every stage of the process, including finding free or low-cost legal help and understanding court notices, logistics and the government’s requirements inside and outside the courtroom.

Without this support, Gavigan has seen people deported who didn’t even realize they were in proceedings that could end in removal.

Asylum case data analyzed by Syracuse University’s TRAC project found that asylum-seekers with legal representation fare better in court. The Northern California Collaborative for Immigrant Justice found that immigrants are 10.5 times more likely to succeed with representation.

TRAC specifically found that those who spoke less common languages are less likely to have attorneys. For example, Mandarin-speaking asylum-seekers had an attorney 79 percent of the time; speakers of Kekchi only had a lawyer 39 percent of the time.

A study published in the Denver Law Review in 2020 found significant ramifications from the lack of access to interpreters in the asylum process: Longer wait times in detention centers, mistranslated interviews leading to case dismissals, or detentions.

In recent years, San Francisco’s pool of migrants has become even more linguistically diverse, said Jose Ng, who co-leads the Language Access Network. He’s now seeing more requests for interpreters who speak Kazakh and Turkmen, for example, two languages he rarely used to see demand for.

Those who can afford it pay about $20 to $50 a page to certified translation services to translate documents, and about $250 an hour to interpreters for in-person meetings.

Those who cannot afford such fees take their chances at submitting documents solely in their native language, which can lead to a case delay or dismissal.

The Bay Area interpreters at the frontlines

Crecencio Ramirez is an interpreter fluent in Mam, a language with 23 recognized dialects spoken by indigenous people in Guatemala and Mexico.

He juggles a packed work schedule: Ramirez works for three Bay Area immigration non-profits and runs Radio Ba’lam in Oakland, the only Bay Area radio station dedicated to serving the Mam community. There are an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 Mam speakers in Oakland, and the number of Mam asylum-seekers continues to rise.

Many of the Mam speakers who find Ramirez have received a “Notice to Appear” from Homeland Security, indicating that they have to appear in court, or face automatic deportation. These notices, Ramirez said, are always written in English.

Ramirez has seen cases, he said, where Mam speakers “couldn’t read the NTA, so they shucked it off to collect dust.” He has seen other people miss their hearings because they couldn’t find someone to translate for them quickly enough.

In her rapid response work, Koren said that one of the “most common issues” is asylum-seekers showing up to their merit interviews without an interpreter, because they did not understand the legal process that had been presented only in English.

Unlike court hearings ordered by a Notice to Appear, a merit interview is part of the affirmative asylum pathway conducted by the USCIS. This interview is the final point for an asylum seeker to present their case in front of a USCIS officer, but it does not provide an interpreter for the session.

The availability and quality of interpretation is “make or break,” said Koren.

Professional services in San Francisco can charge around $1,000 for the merit interview, so many asylum-seekers bring a family or community member to avoid the cost.

One man’s asylum case saved by a last-minute language intervention

On a recent Thursday night, Felipe shared the story of his asylum case at a panel event hosted by Respond Crisis Translation.

In 2022, he fled from Colombia to the Bay Area due to mounting threats of violence against him because of his work as a farmworker activist. He was placed in the affirmative asylum process by USCIS, but ran into trouble when attempting to understand the process in San Francisco.

He clicked on the USCIS page, where he read about the asylum interview in English, but lost critical details due to the language barrier.

As a result, “I showed up to the interview without an interpreter,” he said. The interview was rescheduled and Felipe found a community member to translate for him as he could not afford a professional interpreter.

But, when the day came, the person canceled an hour and a half before the interview.

Felipe said the USCIS officer told him the interview would be canceled entirely if he could not find a substitute interpreter to show up within 15 minutes.

“I was blessed with good luck,” Felipe said, when he ran into Sullivan Engen. She quickly connected him with Koren, who successfully interpreted the interview. He later received asylum.

But others have not had the same good fortune.

Attorney Wahida Noorzad, an Afghani lawyer based in Concord, said that some of her clients who have been able to afford an interpreter have still not had luck. In one case, her client had an interpreter who spoke in their language, Pashtun, but in a different dialect.

In this case, Noorzad quickly identified active mistranslations and began waving to grab the attention of the USCIS officer who asked, “Why are you jumping?”

Noorzad replied, “You’re getting the wrong answers.”

One asylum-seeker’s attempt to receive in-language legal-aid services

On a recent morning inside his courtroom at 630 Sansome St., Judge Joseph Park shook his head in frustration and said loudly, for the second time, “Kazakh!”

“Sorry?” replied the operator for Lionsbridge, the remote translation and interpretation service that contracts with the court.

Park redialed the line once more, in hopes of a better connection. In the courtroom, a 41-year-old man from Kazakhstan waited nervously. In the front bench, his wife sat with their two young children.

“I’m afraid that I have no interpreters in that language,” the operator replied.

Judge Park asked the man if he felt comfortable conducting his proceedings in Russian, the man’s second language. “I have command over both languages,” the man replied, and the hearing proceeded with a Russian interpreter on the line.

Mission Local later spoke over the phone with the Kazakh asylum-seeker with the help of a Russian interpreter.

By law, the man must file any documents in his case with a translator who is certified for the job. Since his court date, he said, he had searched in vain for a Kazakh speaker who could help him through the process — ultimately, he would settle for a Russian translator, against the general advice of asylum attorneys.

“I looked on Google, on Facebook, on many social networks and I didn’t find a Kazakh translator anywhere.” He paused. “Maybe out of a thousand, one will be found somewhere.”